- 1/1

The period was marked by rapid change in terms of both the type and design of the instruments. This is due in no small measure to changes in musical tastes. Classicism brought a desire for a more consistent tonal quality than what was common in baroque music. Virtuosity in performance became an increasingly prevailing ideal, and this called for new technical solutions. The same concerts that had previously been reserved for a privileged class of listeners, were now attended by the middle class. Thus, concerts were performed in ever larger concert halls, and this required instruments that could play louder and fill the hall with sound.

String instruments

Like most other instruments, the strings went through a period of change during the 1800s as they were adapted to changing musical tastes and larger concert halls. Beethoven stood in the midst of this development. Instruments during his time were not as standardised as those we are accustomed to today.

During Beethoven’s era, many of the instruments were the same as those used in earlier baroque orchestras. The string instruments still had gut strings, and they were not equipped with the chin rest, which was developed later.

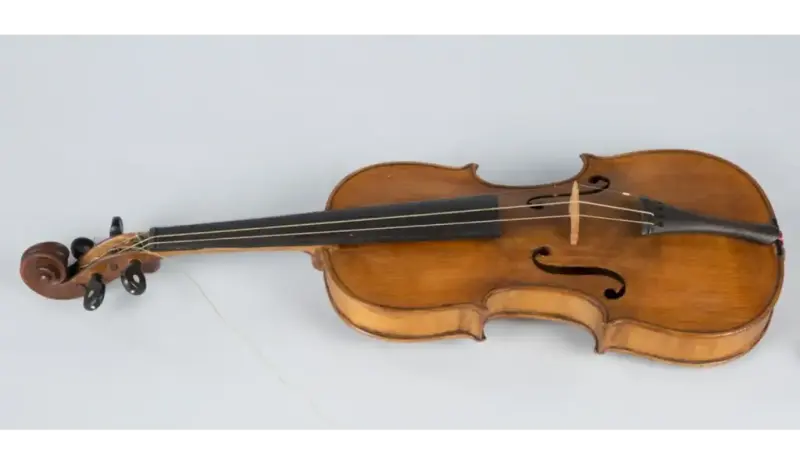

Freia Beer

Freia Beer Violin

This violin was supposedly owned by Peder Ambjørnsen Seivåg, also known as «Spell-Per» [Playing Per] or «Den glade Grei» [Happy Fellow]. In 1911, he rowed a four-oared boat from Frøya in Trøndelag to Oslo to collect 30 kroner that he alleged a member of parliament owed him. He took his violin along in the boat. The trip took 70 days, and he still didn’t get his money. He did, however, get to meet the royal family and play for them, becoming became famous throughout Norway.

Two of the strings are catgut, which was common in earlier times. Otherwise, a label affixed to the underside reveals that the violin was repaired by K. Gunnes in Trondhjem in 1911. It is likely that several aspects of the violin were changed to keep pace with modern tastes.

1800S, maker and place unknown.

Read more on Digitalt Museum.

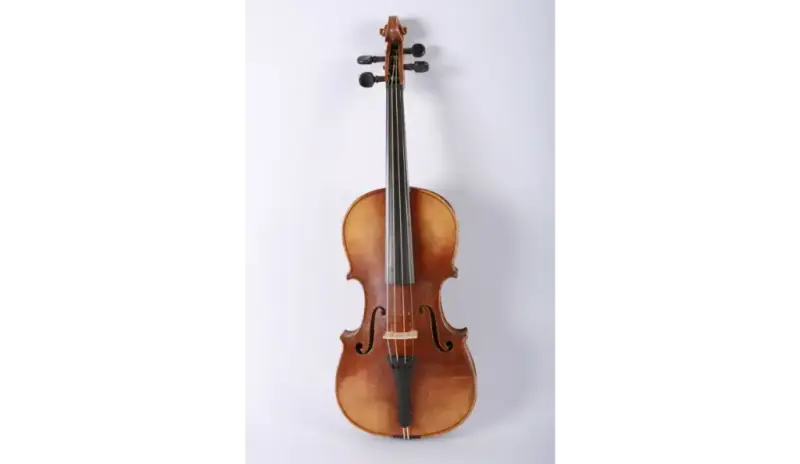

Violin

This violin was probably built after Beethoven’s time, towards the turn of the 20th century, but it has several features that were common during his lifetime. The most striking aspect of this violin is perhaps the fact that it does not have a chin rest. Violinists did not use shoulder rests, either. Certain parts, however, are adapted to the tonal ideal and playing techniques of later times.

Two strings have been replaced with steel strings, while two gut strings remain. The fingerboard, tailpiece and end button are all made of ebony, while the fine-tuning screws are painted black. The tailpiece on this instrument is attached to the end button by a common string, whereas originally it would have been a catgut string.

Likely 1800–1850, maker and place unknown.

Read more on Digitalt Museum.

Viola

This viola was built for the Duke of Alba in the court of King Carlos III in Madrid. It came to Ringve Music Museum in 1967 as a part of the legacy of Adolfo Mopurgo, a Brazilian/Argentine collector. Several pieces have been replaced, such as the tailpiece and the fingerboard. Three of the pegs in the pegbox are original, however.

Vincenzo Ascensio, Madrid (Spain) 1774.

Read more on Digitalt Museum.

Cello

This cello came to Ringve Music Museum in 1967 as part of the Mopurgo collection. The museum’s policy toward the instruments at that time was still influenced by founder Victoria Bachke’s vision of a living museum in which instruments should be heard. The cello, accordingly, was lent out for various performances during the 1970s. An accident that occurred in Vår Frue Kirke (Church of Our Lady) in Trondheim caused damage to the cello, which then underwent several repairs and alterations.

Johann Friedrich Storck, Strasbourg (France) 1769.

Read more on Digitalt Museum.

Contrabass

The most noticeable feature is that this contrabass has only three strings. It originally had four, but the instrument was rebuilt several times. One string was removed and the peghole was sealed off with a brass plate. In addition, the positioning of the pegholes has been realigned. The contrabass has gut strings, a common practice in Beethoven’s time, but the original strings have possibly been replaced. The instrument has also been equipped with a new tailpiece with hanging string, a new oversaddle and a new bridge.

One possible explanation for the reconstruction may be that the wood was attacked by insects, making major repairs necessary. Perhaps the craftsman also seized the opportunity to make other changes to adapt the instrument to the musician’s personal taste and needs.

About 1800, maker and place unknown.

Read more on Digitalt Museum.

Bows

The bows displayed here are distinctly different from one another in appearance. The reason for this is that Beethoven’s era was a transitional period from the established baroque tradition to the beginning of the romantic tonal age.

The bows of the baroque period were thin and light, with a convex bow shape (like bows used for shooting arrows). In Beethoven’s time, many different kinds of bow shapes were in use. The standard bow such as we know it today was not the norm until the early 1800s, through the craftsmanship of bow maker François Tourte (1747–1835). Bows gradually became longer, heavier and increasingly more concave to satisfy demands of higher sound volume in the larger concert halls. Stronger volume demanded higher tension in the bow strings, and concave bows withstand more tension. In addition, the craftsmanship became more refined.

Wind instruments

The wind instruments underwent major changes during the 1800s. A basic improvement was the addition of keys and valves, which enabled a stable timbre and greater virtuosity. Beethoven’s orchestra continued to use many of the instruments that were common during the baroque era, such as trumpets without valves. Woodwinds, however, had begun to be equipped with keys already during the 1700s. Keys were gradually added in increasing numbers, but in Beethoven’s time, there were fewer than today.

Flute

Several aspects reveal that this flute is from the end of the 18th century. Among other things, it is composed of four parts, a common arrangement during the high baroque period, as opposed to the older, three-joint flutes. Other signs are the slightly oval mouth aperture and the size of the bore in the head joint, which is larger than the bore of the foot joint. Keys came along with the baroque, and it wasn’t before the turn of the 19th century that increasingly more keys were added. Nevertheless, it took a long time before flute mechanics were standardised. The process was initiated by Theobald Böhm in 1832. Modern transverse flutes are built based on the Böhm system.

End of the 1700s, maker and place unknown.

Read more on Digitalt Museum.

Clarinet

This clarinet has far fewer keys than the modern clarinets of today, and this lack of keys is a sign of clarinets made in the early 1800s. In addition, the light wood species used was normal in the period and differentiates this instrument from modern ones, which are mostly made from dark hardwood. The instrument can be disassembled into six segments, while modern clarinets usually have only five.

About 1800, maker and place unknown.

Read more on Digitalt Museum.

Oboe

The shape of the oboe clearly resembles its historical forbear, the shawm. It has two keys, which was common during the baroque era. In the course of the 19th century, more keys were added, and the ratio between the pipe and the bell (end joint, or «spout»), was reduced. The instrument is made of boxtree.

About 1800, Goulding&Co., London (Great Britain).

Read more on Digitalt Museum.

Bassoon

The bassoon consists of four individual parts, as was common already in the 1700s. Judging from the few keys on this instrument, their shape and the quality of the instrument as a whole, it appears to date from the early 1800s. It was not until the 1830s that instrument maker Johann Adam Heckel, in Wiesbaden, Germany, developed the so-called Heckel system, which is the most common key system still today.

1810–1840, François-Xavier Proff, Tours (France).

Read more on Digitalt Museum.

Natural Trumpet

The trumpet has no valves, as opposed to modern trumpets. This type of instrument was used in orchestras up into the late 1800s. It is called a Natural Trumpet since it can only play so-called natural tones, that is, tones that are produced only by modulating lip tension and changing tongue position (and hence the velocity of air expelled). The higher one plays on the natural scale, the closer the tones are to one another, until they almost consist of a chromatic scale. This is also why trumpet parts in baroque music are very high, or in the upper register. In Beethoven's music, the trumpet parts no longer play a role as bearers of melody, but instead are more confirmative of the key. They are therefore lower.

1700s, assumed to have been produced in Germany.

On loan from Norwegian Academy of Music.

Natural Horn

About 1850, maker and place unknown

This is a so-called Natural Horn, which means that it emits different tones only via overblowing (altered blowing technique). The tones are situated in natural or overtone registers. Each tonic note (the deepest note in the scale) generates its own register of overtones. To be able to play in different keys, musicians used several different crooks (tubing segments) of various lengths. These enabled different tonic tones.

On loan from Norsk Folkemuseum.

Trombone

The trombone is a replica of a historic baroque instrument. It was built by instrument maker Wilhelm Monke in Cologne, Germany, a city that has been renowned for its replication of historical instruments. Many brass players became associated with Monke so as to contribute towards the development of instruments that were as close to the originals as possible. On this trombone, the bell is the most striking difference. The so-called water key (on the large tubing segment) is nevertheless a compromise in order to adapt the instrument to the demands made on performers to be able to remove accumulated fluid.

Early 1960s, Wilhelm Monke, Cologne (Germany).

Drums

Timpani

The timpani are made of copper, cast iron and calfskin leather. They were manufactured about 100 years after Beethoven’s death, but the craftsmanship and mechanics correspond to the standard during Beethoven’s lifetime.

What primarily indicates the various phases in the development of the timpani are the tuning mechanisms. The tuning mechanism with metal rings and screws such as we see here were added after the discovery of chemical reactions that could remove the hair from calfskin. The leather hide was thus much thinner; it could no longer be kept in place with twine and had to be held in place with metal rings. Thus, it became possible to tune the timpani by altering the pressure from the rings, and thereby the skin tension, with the aid of screws.

Early 1900s (probably 1920s), Oskar Ullman, Leipzig (Germany).

On loan from a private collection.

Keyboards

Fortepiano

During Beethoven’s lifetime, keyboard instruments were being developed at a furious pace. The harpsichord of the Baroque era had a percussive sound and limited dynamic expression and varied tonal volume. This disadvantage was overcome by the fortepiano, the predecessor of the modern-day piano. Beethoven himself, a star pianist and improviser, contributed to this development. He pushed the instrument to its limits and was always looking for new technology that might provide even greater musical expression through fuller sound and dynamic contrasts. The opportunity to play both loudly (forte) and softly (piano) was the origin of the term fortepiano, abbreviated today as merely piano.

Broadwood & Sons, London 1823